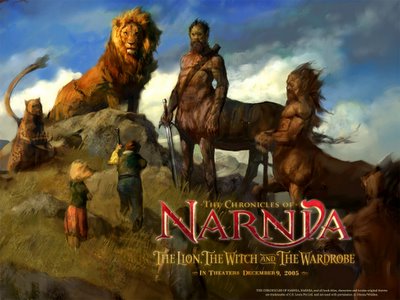

The film version of C. S. Lewis's The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe opens today in theaters around the world. Sarah and I have made arrangements for our little son of Adam to spend the evening with friends (thanks, Alex and Emily!), and we're off to see the movie with friends from church this evening.

The film version of C. S. Lewis's The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe opens today in theaters around the world. Sarah and I have made arrangements for our little son of Adam to spend the evening with friends (thanks, Alex and Emily!), and we're off to see the movie with friends from church this evening.The reviews have been flying off the presses for the last week or so, most of them positive. Nevertheless, the movie seems to have come out as explicitly "Christian" enough to smell like death to certain reviewers (see the particularly noxious and ill-informed bit of hate speech by Polly Toynbee of the Guardian; cf., 2 Cor. 2:15-17).

For a more sympathetic treatment, check out the review by Frederica Matthewes-Green at at beliefnet. "Mama Fred" always has something good to say, and here she draws our attention to

the way Lewis narrates the atonement. The Western tradition, since Anselm (1033-1109), has generally described Aslan's sacrifice as a debt, paid on behalf of humanity, to satisfy the justice of the Emperor over the Sea. The Witch does not figure large in this understanding; rather, the Passion of the Lion is seen as a transaction between members of the Trinity on behalf of the sons and daughters of Adam and Even. This view is strong on the Trinitarian nature of the atonement, but rather weak on the narrative aspect. As Matthewes-Green points out, however, Lewis's retelling seems to follow more closely to the older, Eastern understanding of the atonement, especially as elaborated by Gregory of Nyssa (d. 385/6). On this reading, Aslan tricks the Witch into taking the bait, and her own greed is her undoing: the finite (i.e., evil) tries to swallow up the infinite (i.e., God), which it cannot contain--at least not for more than three days! This view is strong on the narrative aspect of the atonement and in representing the Lion's work as liberating his people from the power of sin. It is weak on the Trinitarian themes, however (at least in Lewis's retelling)--after all, where is that distant Emperor over the Sea? And the Holy Spirit? Is there a Holy Spirit in Narnia?

the way Lewis narrates the atonement. The Western tradition, since Anselm (1033-1109), has generally described Aslan's sacrifice as a debt, paid on behalf of humanity, to satisfy the justice of the Emperor over the Sea. The Witch does not figure large in this understanding; rather, the Passion of the Lion is seen as a transaction between members of the Trinity on behalf of the sons and daughters of Adam and Even. This view is strong on the Trinitarian nature of the atonement, but rather weak on the narrative aspect. As Matthewes-Green points out, however, Lewis's retelling seems to follow more closely to the older, Eastern understanding of the atonement, especially as elaborated by Gregory of Nyssa (d. 385/6). On this reading, Aslan tricks the Witch into taking the bait, and her own greed is her undoing: the finite (i.e., evil) tries to swallow up the infinite (i.e., God), which it cannot contain--at least not for more than three days! This view is strong on the narrative aspect of the atonement and in representing the Lion's work as liberating his people from the power of sin. It is weak on the Trinitarian themes, however (at least in Lewis's retelling)--after all, where is that distant Emperor over the Sea? And the Holy Spirit? Is there a Holy Spirit in Narnia?Lest we think that we are left with a stark opposition between Eastern and Western theories of atonement, however, Lewis's story does give some hints as to how the two may be resolved.

The key lies in the fact that the actions of all the characters--both the Witch and Aslan--are governed by law. When Aslan comes to claim Edmund, the Witch responds with an assertion of her right to the victim: "Unless I have blood, as the Law demands, all Narnia will be overturned and perish in fire and water." Aslan could, of course, just gobble the Witch up in one gulp and have done with it. But he doesn't. Aslan assents to this demand, because it is his law--to break it would be to contradict his own character, and negate his creation. But--and here's the hook--there is a "deeper magic," of which the Witch knows nothing: "When a willing victim who has committed no treachery is killed in a traitor’s stead, the Stone Table would crack and even death itself would turn backwards."

The key lies in the fact that the actions of all the characters--both the Witch and Aslan--are governed by law. When Aslan comes to claim Edmund, the Witch responds with an assertion of her right to the victim: "Unless I have blood, as the Law demands, all Narnia will be overturned and perish in fire and water." Aslan could, of course, just gobble the Witch up in one gulp and have done with it. But he doesn't. Aslan assents to this demand, because it is his law--to break it would be to contradict his own character, and negate his creation. But--and here's the hook--there is a "deeper magic," of which the Witch knows nothing: "When a willing victim who has committed no treachery is killed in a traitor’s stead, the Stone Table would crack and even death itself would turn backwards."I still get chills every time I read that sentence. It lies very near the heart of the Christian Gospel. Evil--Satan himself--plays a part in a drama that is not of his own making. As Luther understood so clearly, the Devil is "God's Devil"--like a dog on a chain, he can act only by God's permission. And, like the White Witch, he is permitted to act only in such a way as leads to his ultimate undoing--and to the liberation of the sons and daughters of Adam and Eve from sin and death. We human beings do indeed owe God a debt we cannot pay--we have exchanged the glory of God for a bit of Turkish Delight. The devil, sin, and death are God's collection agents. But Christ has broken their power and sealed their doom. That is what the "deeper magic" is all about: God's mercy and his justice are not ultimately in conflict.

But don't take my word for it: go see the movie. (And if you can't find a babysitter for tonight, here's a link to whet your appetite a bit more)

5 comments:

My pastor is doing a three week series (starting last week) on Narnia, and made the point that Lewis didn't intend to create an allegory, but rather a supposal. I still don't know what that means. Might you? He explained what that meant, but now I've forgotten.

Who read us "The Lion ..." in elementary school? Was it third grade?

Hmm. I've heard this, too. This may be a bit finer distinction than I know how to make, but it looks like an allegory to me. Tolkien sure thought it was an allegory. Is your pastor entering his sermon in the contest for the free trip to England?

As for CRCS, I don't remember if it was read to us. Do you? Were you around in third grade?

yeah ... i think it was written to us by Mrs. Sams (sp?) in third (my final year at that fine institution). I think Lewis himself said that it was a supposal to a group of grade-schoolers. I don't think he's submitting his sermon. He could have no higher honor than being preacher of the semester twice at TEDS;o).

David,

I'm so glad you liked it. That's good to hear. Hopefully, Maria and I will have a chance to get to it before it leaves the theaters. Joshua's feeding schedule wouldn't allow it presently.

Post a Comment